On Antifragility and Independence

“He who builds his house on sand will see it crumble (cf. Matthew 7:24-27, Luke 6:47-49, Proverbs 10:25-32).”

“The only real security that a man can have in this world is a reserve of knowledge, experience, and ability.” – Henry Ford

“Only when the tide goes out do you discover who has been swimming naked.” – Warren Buffett

For decades, globalization, outsourcing, and interconnected supply chains have been hailed as the cornerstone of economic progress. Nations built economies on the assumption of never-ending American support, just as corporations reaped “cost savings” via outsourced manufacturing. Investors too are guilty, as we have grown over-reliant on management team quarterly guidance, monetary policy “puts”, and seemingly unending fiscal stimulus, effectively “outsourcing” our own independent thought. The result has been a growing complacency in markets, a false sense of stability as we mistake fragile interdependence for robust and resilient economic development and investment processes. But the world is changing: sovereigns are retrenching, capital flows are shifting, and companies are now scrambling to regain control of their processes that have been ceded over decades. Said differently, the illusion of stability is breaking.

The past few years have exposed an uncomfortable truth: dependence breeds fragility. The ability to thrive, as a nation, as investors, and as individuals depends not on external reliance but internal strength, adaptability, and the capacity to endure. Independence, in that way, isn’t just a virtue, but a necessity for survival.

In this essay, I argue that the illusion of stability created by globalization has bred fragility, and that nations, investors, and individuals must embrace an Antifragile framework characterized by decentralized command, self-sufficiency, and optionality to navigate what is certain to be an uncertain future.

The Case for Globalization

The bull case for globalization is clear: a larger addressable population means a bigger labor pool which means more (and cheaper) production which means more profits. Naturally, the largest nations and corporations benefit most from this as the reserve status of the US Dollar allowed for labor and production cost arbitrage while multi-national corporations (MNC) leverage economies of scale.

The case was even clearer during the post-Depression, post-WWII rubble. After the experience of the Great Depression, characterized by economic isolation and retrenchment, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced the entitlements system which was a way for the domestic government to “step in” in times of economic hardship. That recency bias in policymaking was also seen post-WWII, as the demolition of continental Europe made it clear that global cooperation was the only way to rebuild, leading to the creation of global intermediaries who too would be able to “step in” in times of international economic hardship (via the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank post the Bretton Woods agreement in the 1940s)1, 2.

While many view globalization as a more recent phenomenon, it is in truth part of a much longer timeline. For centuries, humans have sought to expand their horizons via geographic expansion, trade, and manifest destiny. From the Silk Road to the Age of Discovery to today’s hyper-globalized consumerism exemplified by Temu and Shein, globalization has been an enduring yet highly cyclical force.

In an idealized, utopian world, global cooperation and the free flow of capital benefits all parties: consumers get access to goods and services that may not be available domestically, businesses expand their reach and improve efficiency, and governments enjoy the economic and diplomatic advantages of interdependence. However, while globalization has driven unparalleled economic growth, its reliance on stability and cooperation has also introduced profound vulnerabilities.

The Inherent Fragility of Globalization

“The four most expensive words in the English language are 'This time is different'" - Sir John Templeton

Despite its numerous benefits in times of stability, there is one thing that is consistent through recorded history: a lack of stability. Akin to “death and taxes”, geopolitical conflict and tension too has been a certainty of international relations. What do we expect to happen in an increasingly interconnected world where millions of people from differing value structures intertwine?

A brief look through history brings to the surface centuries of ongoing conflict leading to the ebb and flow of global expansion and contraction:

- 130 BCE – 1454: The Silk Road trade routes that connected the ancient world weakened due to the Crusades (1100-1400) and the Black Death (1340-1350), disrupting relations between Europe and the Middle East and culminating with the rise of the Ottoman Empire, which drove Europe to seek alternative routes as overland trade became unfeasible3,4

- 1400 – 1700: The Renaissance, characterized by weakened religious dominance and the rise of monarchs, led to the Age of Discovery where Europeans sought new maritime trade routes to bypass Ottoman control, which sparked rivalry in Europe as the chase for global dominance ensued, ultimately culminating with the discovery of the Americas5

- 1700 – 1900: The Industrial Revolution (IR) spurred voracious demand for raw materials, giving way to nationalized trading companies and colonial empires6; Rapid economic growth and development led to the breakdown of monarchies, while financial markets and the rise of laissez-faire capitalism marked a new era of economic expansion7,8

- 1900 – 1945: The economic expansion of the IR fueled global competition, contributing to rising nationalism during the early 20th century; nationalistic tensions manifested with World War I and World War II, as nations sought to assert dominance and expand influence, leading to mass carnage and subsequent economic contraction9

- 1945 – 2007: Following the carnage of 50 years of world wars, Bretton Woods sought to drive international cooperation, disincentivizing the nationalism which drove such hardship in the half-century prior, and gave way to the rise of international institutions, trade agreements, and global integration, an expansion that continued well into the 21st century10

- 2008 – 2019: The Great Financial Crisis (GFC) was the most prominent modern-day example of the fragility of globally intertwined markets, as the financial collapse of US housing rippled through the broader world economy; International exposure to the US housing sector drove aftershocks for the next 5 years, leading to a series of Eurozone debt crises from 2009-2012, and subsequent economic contraction11

- 2019 – present: The COVID era again shocked global trade and international cooperation, revealing vulnerabilities in supply chains assumed to be robust and invulnerable, prompting countries to reconsider their dependence on globalized production networks; further fueled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s aggressive stance on Taiwan, and the US shifting closer to nationalism, we find ourselves today in an era of “de-globalization”

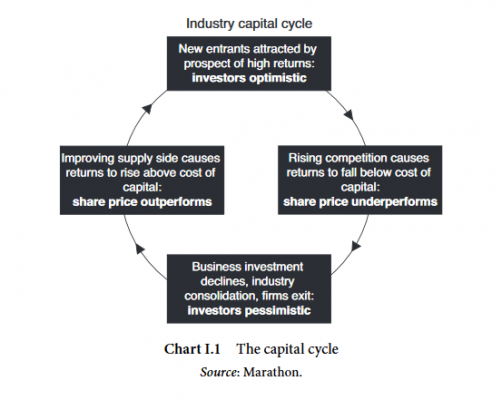

Reminiscent of Marathon Asset Management’s brilliant Capital Cycle framework12 (illustrated in the below, left-side chart), the ebb and flow of global expansion has persisted for many centuries. In stable times, nations expand international trade in pursuit of increased economic development. Said expansion creates competition for dominance, which leads to tension. Said tension leads countries to embrace nationalism and isolationism. Said isolationism leads to global contraction. As the dust settles, nations engage again with global peers, and so the cycle continues.

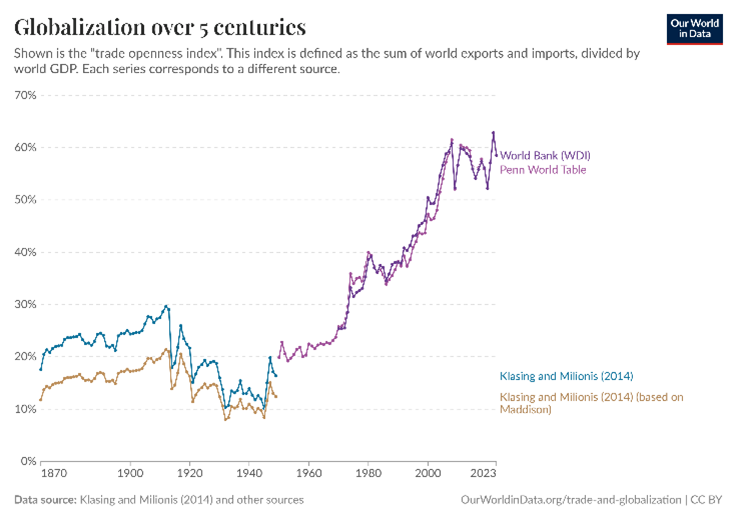

Despite its intellectual intentions for good, globalization has proved to be anything but a linear path toward global prosperity and flourishing. As we consider the absolute level of interdependence (as displayed in the above, right-side chart9), we must be prepared for additional bouts of tension and contraction. To successfully navigate such volatility, we must embrace principles that not only resist shocks but thrive on them. In short, we must build Antifragility into our approach to economics, markets, and life.

Navigating the Unknown

Nassim Nicholas Taleb offers insight in Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. In it, he defines Antifragility as “beyond resilience or robustness” and suggests that the antifragile get stronger from chaos rather than just merely survive through it. The concept of Antifragility has applications in life as well as in markets and includes things like avoiding excess leverage (in life and markets), owning the means of production (in economics and markets), and resistance training (in personal health and wellness). A few overarching characteristics of Antifragility help us illuminate the way forward:

- Decentralization. A primary theme in the history of nations and markets has been the failure of centralized command and central planning. Whether debating the merits of Capitalism v. Socialism, Bureaucratic v. Lean operations, Federal v. State legislative regimes, or even military command, the theme remains true that centralized command increases the fragility of a system. Conversely, by continuously pushing down decision making to the individuals closest to the consequences of the outcome, we breed Antifragility. Decentralized command is seen in some of the most successful companies (Berkshire Hathaway and Heico, for example), successful military operations (Joint Special Operations Command, JSOC, popularized by Jocko Willink), and even the philosophy behind Bitcoin, sound-money protocols.

- Skin in the game. The late Charlie Munger famously said, “show me the incentive, I’ll show you the outcome”. Operators with skin in the game aren’t just managing from their ivory tower but instead are incentivized to act in the best interest of the whole, be it a sovereign, a corporation, an investment fund, or even interpersonal relationships. Without proper incentives, there are limited downstream impacts from acting in ill-mannered ways, thus increasing fragility.

- Avoiding existential risks. The legendary duo, Buffett and Munger, often talk about this principle too. Warren’s top rules of investing (#1 don’t lose money, #2 don’t forget #1) and Charlie’s famous quip “All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll never go there”, highlight the concept better than I ever could. If we are aware that we cannot possibly be aware of unknowns, we can better position ourselves to thrive from those unknowns, rather than be wiped away by them. Evolutionary biology too gives us reason to practice defense and prudence, as those species who have survived for millions of years generally had better defense mechanisms than offense mechanisms13. Even the world of sports offers insight with the famous quote “Offense wins games, defense wins championships”.

- Self-sufficiency. The principle of self-sufficiency can be seen with companies (organic growth, net cash balance sheets or low debt loads, vertical integration, owned real estate, etc.) as well as individuals (personal skill-building, financial independence, exercising body and mind). Self-sufficiency doesn’t rely on the Fed cutting interest rates or the government stepping in with “stimmy”. True self-sufficiency isn’t about isolation, but mastering process, philosophy, and discipline (Quality), knowing your “game” and playing it on your terms.

- Embracing optionality. If the only certainty is uncertainty, seeking optionality is the smartest course forward. Whether this is a corporation owning its land and production capabilities or an individual stowing away cash for the proverbial “rainy day”, optionality is our “buffer” to chaos. In a famous exchange from the GFC, a Former Citigroup Chief Executive famously quipped “As long as the music’s playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing” … that was in July 2007, just four months before he resigned. By November 2008, Citigroup needed a $45bn bailout to prevent its collapse14,15. A painful reminder that ignoring optionality in the pursuit of short-term gains is a recipe for disaster.

As we face a future marked by volatility, both in markets and in life, the principles of Antifragility – decentralization, self-sufficiency, and embracing optionality – are not just philosophical ideals, but practical tools for survival and success. Nations, investors, and individuals who continue to place their trust in centralized systems of global interdependence will increasingly find themselves vulnerable to the inevitable ebbs and flows of cycles. To thrive in an uncertain world, we must build systems that don’t just withstand disruption, but strengthen because of it.

1 Federal Reserve History. “Bretton Woods Created.” Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/bretton-woods-created

2 U.S. Department of State. “The Bretton Woods Conference, 1944.” Office of the Historian. https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/wwii/98681.htm

3 World History Encyclopedia. “Silk Road.” World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/Silk_Road/

4 UNESCO. The End of the Silk Route. https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/the end of the silk route.pdf

5 Britannica. “European Exploration.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/European-exploration/The-emergence-of-the-modern-world

6 Britannica. “East India Company.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/East-India-Company

7 Nairn, Alasdair. Engines That Move Markets: Technology and the Transformation of the Global Economy. 2nd ed. Wiley, 2017.

8 Greenspan, Alan. Capitalism and America: The Moral Foundations of Economic Growth. Penguin Press, 2018.

9 Our World in Data. “Trade and Globalization.” Our World in Data ttps://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization

10 U.S. Department of State. “Bretton Woods.” Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/bretton-woods

11 European Parliament Research Service. The Future of Globalization: Brexit, Trump, and Economic Nationalism. 2019. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/642253/EPRS_BRI(2019)642253_EN.pdf

12 Chancellor, Edward, ed. Capital Returns: Investing Through the Capital Cycle: A Money Manager’s Reports 2002–15. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

13 Prasad, P. What I Learned About Investing from Darwin: Using Evolutionary Science to Navigate the Markets. Columbia Business School Publishing, 2023.

14 Reuters. “Ex-Citi CEO Defends Dancing Quote to US Panel.” Reuters https://www.reuters.com/article/markets/funds/ex-citi-ceo-defends-dancing-quote-to-us-panel-idUSN08198108/

15 Reuters. “Citigroup Gets Massive Government Bailout.” Reuters https://www.reuters.com/article/world/citigroup-gets-massive-government-bailout-idUSTRE4AJ45G/

Member discussion